Introducing the NEMESIS Online Course! (MOOC)

Everything you need to know to get to grips with Social Innovation Education and how to deliver it!

NEMESIS has already brought you the Replication Handbook – a comprehensive guide to help you understand Social Innovation Education (SIE) and how to get it going in your school. It includes everything from the philosophy behind SIE, the benefits for all involved and how to plan and run your very own Co-creation Lab.

As fans of collective action, this handbook is not alone! It works alongside the Resource Bank – a resource that is choc full of activities for you to use and adapt at every step of your lab. There are so many to choose from that you may need a starter menu so schools and teachers already using SIE told us their favourites and we’ve marked these with an N – why not try those ones first?

And finally, the second annex to the handbook includes a wide range of inclusive practice that’s taken place during the 3.5 year NEMESIS project. Teachers and School Leaders from all over Europe who’ve already implemented SIE in their schools shared their insights and practice as inspiration to help new users tailor their approach to SIE and Co-creation Lab (where the SIE magic happens!) to suit their context and students.

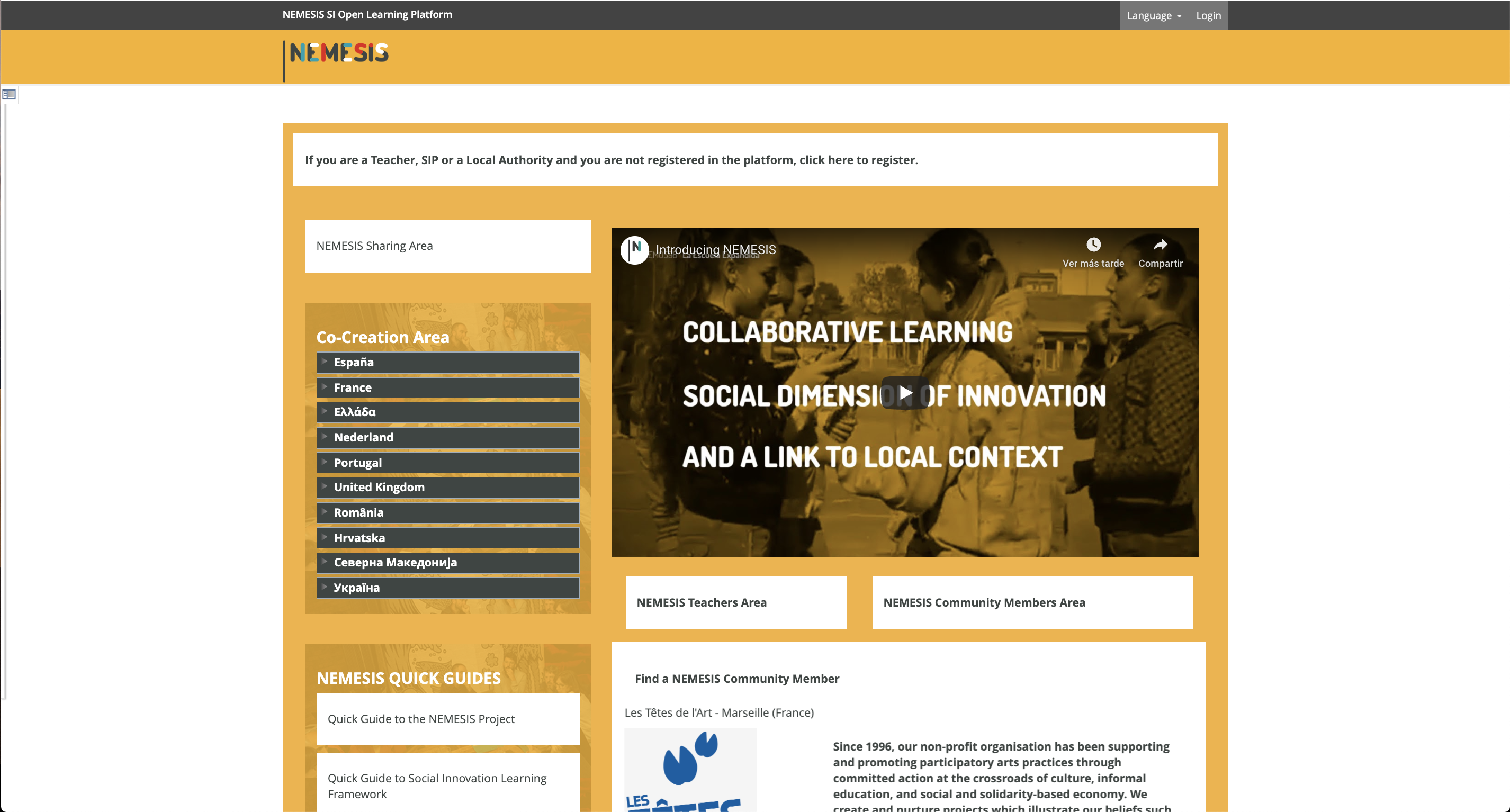

Now, enter the MOOC! This Massive Open Online Course is free and available to all. It offers an 8 module course that takes you through SIE from start to finish in both an informative and interactive way.

Setting off

Start your SIE journey by getting to grips with the theory and philosophy behind SIE – how this innovative pedagogy came about to tackle inequality in society by using the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to guide young people in identifying and addressing social issues in their local area. Find out the numerous benefits for all involved such as the opportunity for young people to drive a project to create sustainable social value, connect with a diverse group of people and have fun along the way!

Teachers and School Leaders already using SIE share invaluable insights through interviews and case studies on how to prepare young people to take part, whether that’s through the curriculum, attached to an existing initiative, such as Citizenship Education, or in extra-curricular activities. You’ll get to know the Social Innovation competence framework and choose which competences, such as empathy, collaboration, critical thinking (or a combination of more!) your young people would most benefit from developing and then learn how to put these into action through starting your very own Social Innovation project!

You’ll get examples and suggestions on how to enthuse young people about SIE and links to materials, such as promotional leaflets, that you can download for free to give young people and adults alike a flavour of what they’ll get from taking part in SIE.

Full steam ahead!

The MOOC has a very practical approach so not only will you be introduced to what SIE is but also how to deliver it in your educational setting. After getting to grips with the reasoning behind SIE, the modules take you through how to set up and facilitate a Co-creation Lab. You’ll be introduced to each step of a lab:

- preparing for the lab

- getting to know each other

- understanding social innovation

- identifying a social issue

- planning how to address the issue

- carrying out your project

You’ll get a practical checklist of how to prep for your first lab and will get to know activities from the Resource Bank to use for each step. There’s reference materials for the Sustainable Development Goals and activities to get you and your young people familiar with them. There’s links to the NEMESIS platform so you can find people involved in Social Innovation if you fancy being inspired by real life Social Innovation or there are activities to help deepen understanding instead. Mix and match – it’s up to you!

At the end of each module, there’s a short quiz or place where you can add to your personalised Co-creation Lab plan, so you are ready to go with a plan of action by the end of the MOOC.

Sharing your Social Innovation Education journey

For each step of SIE, activities and ways of documenting your journey are suggested so you can reflect, share and see how far you’ve come – always a great feeling and super motivating for all involved (see some success stories on the project page). And you can add your digital story to the NEMESIS Community on the platform to share your legacy and connect with people all over Europe.

We hope you enjoy the MOOC and can’t wait to see your very own digital stories of how your young people changed the world!

What has evolved out of the first year’s evaluation was the fact that the

What has evolved out of the first year’s evaluation was the fact that the

Evaluation insights have shown that students have evolved from a position of ignorance to a position of interest and positive consideration towards the activities they were involved in and the ideas they were discussing. As such, they think that their learning makes a difference to their community and the wider world (vision for a better world). As the project and their activities evolved, students were able to envisage a better world by focussing on aspects they find unpleasant. Many students seemed to find it easier to think about ‘big’ problems such as world hunger, but they did not immediately view ‘smaller,’ more local issues as a problem that needs solving. Whenever the engagement of external stakeholders was constant and meaningful to them, students felt more motivated and highly inspired and were bursting with ideas about how to make the world a better place by simply following their examples.

Evaluation insights have shown that students have evolved from a position of ignorance to a position of interest and positive consideration towards the activities they were involved in and the ideas they were discussing. As such, they think that their learning makes a difference to their community and the wider world (vision for a better world). As the project and their activities evolved, students were able to envisage a better world by focussing on aspects they find unpleasant. Many students seemed to find it easier to think about ‘big’ problems such as world hunger, but they did not immediately view ‘smaller,’ more local issues as a problem that needs solving. Whenever the engagement of external stakeholders was constant and meaningful to them, students felt more motivated and highly inspired and were bursting with ideas about how to make the world a better place by simply following their examples. to improve them. However, the level of evaluating those ideas and responsibly acting towards accomplishing their goal was not that evident (responsible and critical thinking). This was expected given the different and, sometimes, challenging subjects that each of the schools and classes have been working on. Nevertheless, students have gained an increased sense of belonging and ownership. The fact that they are raising their voice and they have been heard making at the same time decisions of their own is of great value to them and make them more responsible and critical towards the subject they are focusing on.

to improve them. However, the level of evaluating those ideas and responsibly acting towards accomplishing their goal was not that evident (responsible and critical thinking). This was expected given the different and, sometimes, challenging subjects that each of the schools and classes have been working on. Nevertheless, students have gained an increased sense of belonging and ownership. The fact that they are raising their voice and they have been heard making at the same time decisions of their own is of great value to them and make them more responsible and critical towards the subject they are focusing on. AEMAIA (Portugal) has referred to her own experience, asserting that at first, she was unsure about her role but then her confidence and self-efficacy was building gradually. She was really surprised because initially she expected teachers would tell her what to do but that was not the case.

AEMAIA (Portugal) has referred to her own experience, asserting that at first, she was unsure about her role but then her confidence and self-efficacy was building gradually. She was really surprised because initially she expected teachers would tell her what to do but that was not the case.

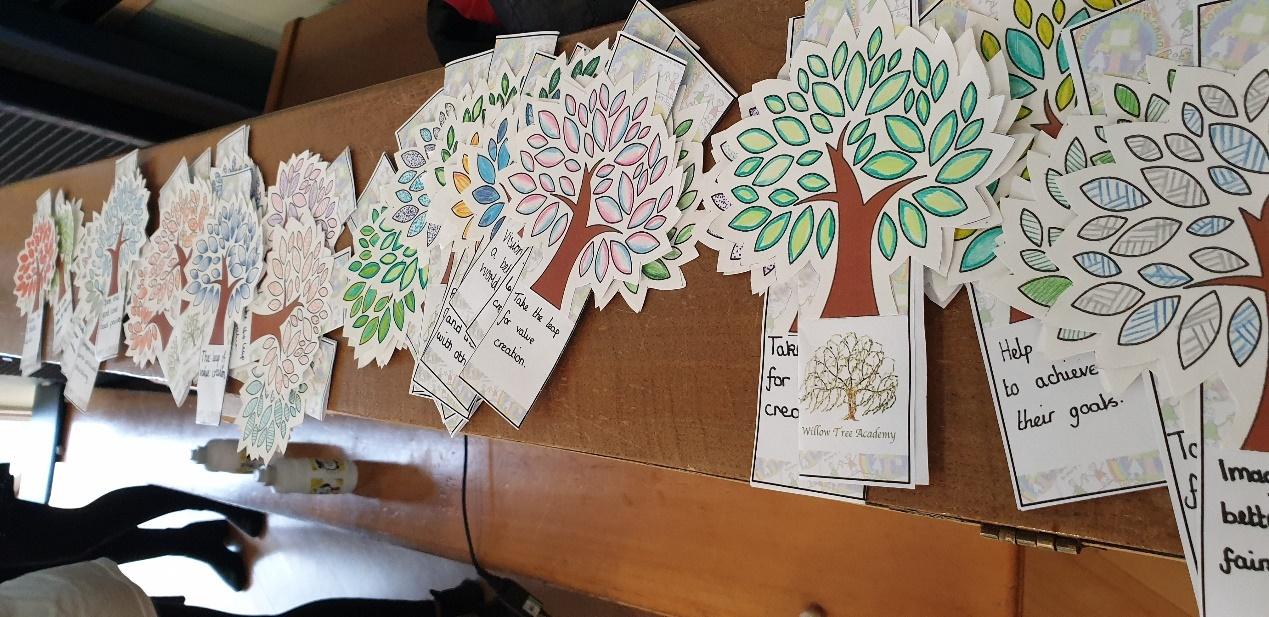

As such, the competences and values we envision in NEMESIS include self-efficacy and social communication skills but also temper them with empathy and the embracing of diversity and democratic decision-making. Our model promotes problem-solving skills and resource mobilization abilities, but also pairs them with reflective learning and social resilience. In its ethical core, NEMESIS aims to encourage the development of collective capacities for taking innovative actions inspired by key values, such as equality, respect, generosity, trust and altruism. When such results become evident through our collective efforts in the NEMESIS project, we will know that our tree is blooming and is about to bear fruits. Youth activism goes beyond charitable and voluntary work for the community, it aims at influencing policy and institutional practices for the promotion of social justice.

As such, the competences and values we envision in NEMESIS include self-efficacy and social communication skills but also temper them with empathy and the embracing of diversity and democratic decision-making. Our model promotes problem-solving skills and resource mobilization abilities, but also pairs them with reflective learning and social resilience. In its ethical core, NEMESIS aims to encourage the development of collective capacities for taking innovative actions inspired by key values, such as equality, respect, generosity, trust and altruism. When such results become evident through our collective efforts in the NEMESIS project, we will know that our tree is blooming and is about to bear fruits. Youth activism goes beyond charitable and voluntary work for the community, it aims at influencing policy and institutional practices for the promotion of social justice.