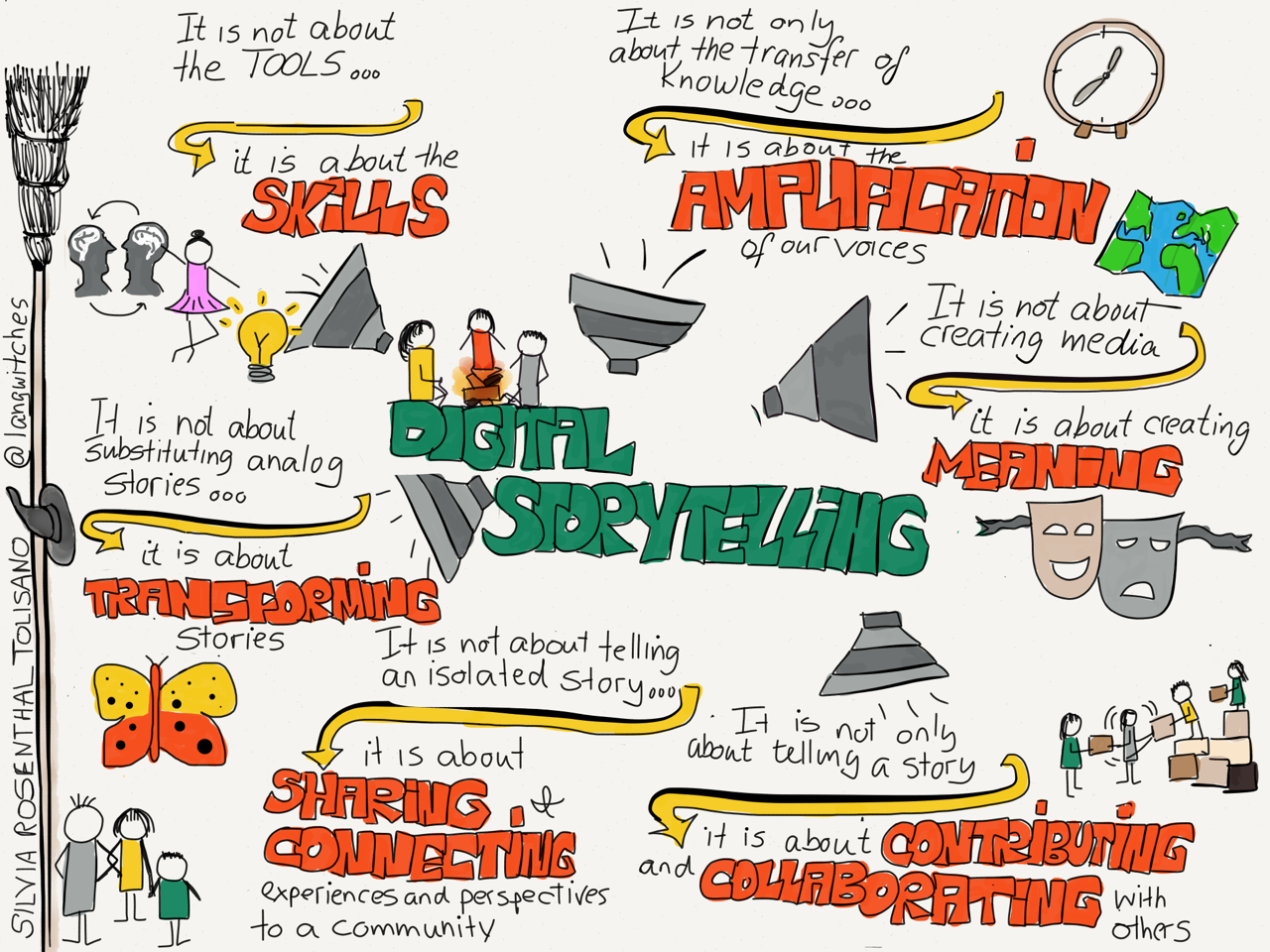

What is digital storytelling and what is not?

Digital storytelling has its origins in one of the oldest arts in the history of mankind – telling stories. It is based on creating and telling or sharing narrations using not only words, but also modern IT tools and multimedia materials like: graphics, video, audio, animation. As Silvia Rosenthal points out in her article “Digital Storytelling: What it is and What it is not”:

“Humans are natural storytellers. It has been THE FORM of passing on knowledge from generation to generation. Storytelling existed in some shape or form in all civilizations across time. In the 21st century, which we have the luck to live in, Digital Storytelling, has opened up new horizons, inconceivable without the use of technology. Storytelling is evolving, as humans are adapting, experimenting and innovating with the use of ever-changing technology, the growth of human networks and our ability to imagine new paths”.

Nowadays, storytelling is still widely used in education and in everyday life. However, the development and the widespread use of technology has changed the tools we can use to tell a story. The use of ICT tools in creating and sharing stories has changed the range and impact that such stories might have. Further, it has allowed us to reach larger audiences and its impact might be much more effective.

It is not just about the tools. It is about the skills

Jenna McWilliams, who participates in the project of New Media Literacies, describes in a very graphic way the idea of reading with a mouse in your hand. She says that sometimes teachers encourage students to read with a pen in their hand. It is about committing themselves critically, taking notes, raising questions, thinking, rather than simply looking at the words. Likewise, when students read with a mouse in the hand they take one more step: they assume that they must actively respond to what is in front of them; they are pushed to participate, to be responsible for the quality of the information they receive and to correct it publicly, if it is incorrect.

It is not about creating media. It is about creating meaning

More and more content is shared on the Internet over time. It is valuable to contribute our perspectives to a type of content but is much better if the emphasis of the stories we share create some meaning— and make that meaning visible to others — not the act of creating the content itself. We found a wonderful example with this teen user of TikTok. She expresses a heartbreaking criticism of the mass detention of Muslim Uighurs in China, in the format of a makeup tutorial. We take our hat off to her.

It is not only about telling a story. It is about contributing and collaborating with others

Thanks to the Internet educators are able to collaborate and share ideas and information all over the world. Without question, Twitter could be a very rich source of information, but the feed moves pretty fast. As a result, the information can be difficult to keep up with.

Twitter chats are conversations to add value to other people’s learning. Chats take place on a specific topic on a specific day and at a specific time. Participants in the chat use a #hashtag specific to that topic, which allows for a search to be conducted even after the chat has ended. There are plenty of them related to education.

A Twitter chat is a scheduled, organised conversation on Twitter centred around a specific topic and hashtag – @EUErasmusPlus is organizing one for #teachers next week! ? https://t.co/t3OuyaInOu

— NEMESIS – Social Innovation Education (@nemesis_edu) July 11, 2019

It is not about telling an isolated story. It is about sharing and connecting experiences and perspectives to a community

Me Too is the name of a virally initiated movement that emerged as a hashtag in October 2017. It was created to denounce sexual harassment, following accusations against Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein. Many celebrities used the hashtag to tweet their experiences and demonstrate the widespread nature of misogynist behaviour. In other words, #metoo movement triggered a global cry of women, proving that the problem was not a simple aggregation of individual stories. #Metoo has been the evidence of a structural issue beyond far the film industry.

It is not about substituting analogue stories. It is about transforming stories

Digital storytelling, because of its technological component, has allowed new forms of interactivity. Interactive stories enable us to experience different routes based on the options we choose. For example, the project CHESS (Cultural Heritage Experiences through Socio-personal interactions and Storytelling), co-funded by the European Commission, aims to implement and evaluate both the experiencing of personalized interactive stories for visitors of cultural sites, facing the important challenge of making their collections more engaging to visitors, especially the young ‘digital natives’, while exploiting new forms of cultural interactive experiences.

In conclusion

So, conceived like this, Digital storytelling is not about how to make the most professional video ever. Digital storytelling is about different types of skills that are developed in the process, that allow students and teachers to be engaged and critical digital media consumers. Just like what we do in a social innovation project in a school. The main objective is not that the student learns how to paint a patio or garden, or how to organise a second-hand market. The clue is the process during which they can develop skills. For example identifying opportunities that create social value or forming and valuing new cohesive relations and collaborations.

This article is an extract of the Teacher’s Guide to Digital Storytelling.

Digital Storytelling is an integral part of NEMESIS as it is a learning tool as well as a way to document and showcase the work created in the Co-creation Labs. Is a way to document and share your social innovation project in a participative way. Read our Teacher’s Guide to Digital Storytelling for further information: https://nemesis-edu.eu/about/resources