Stakeholder engagement in NEMESIS: Lessons from Pilot 1

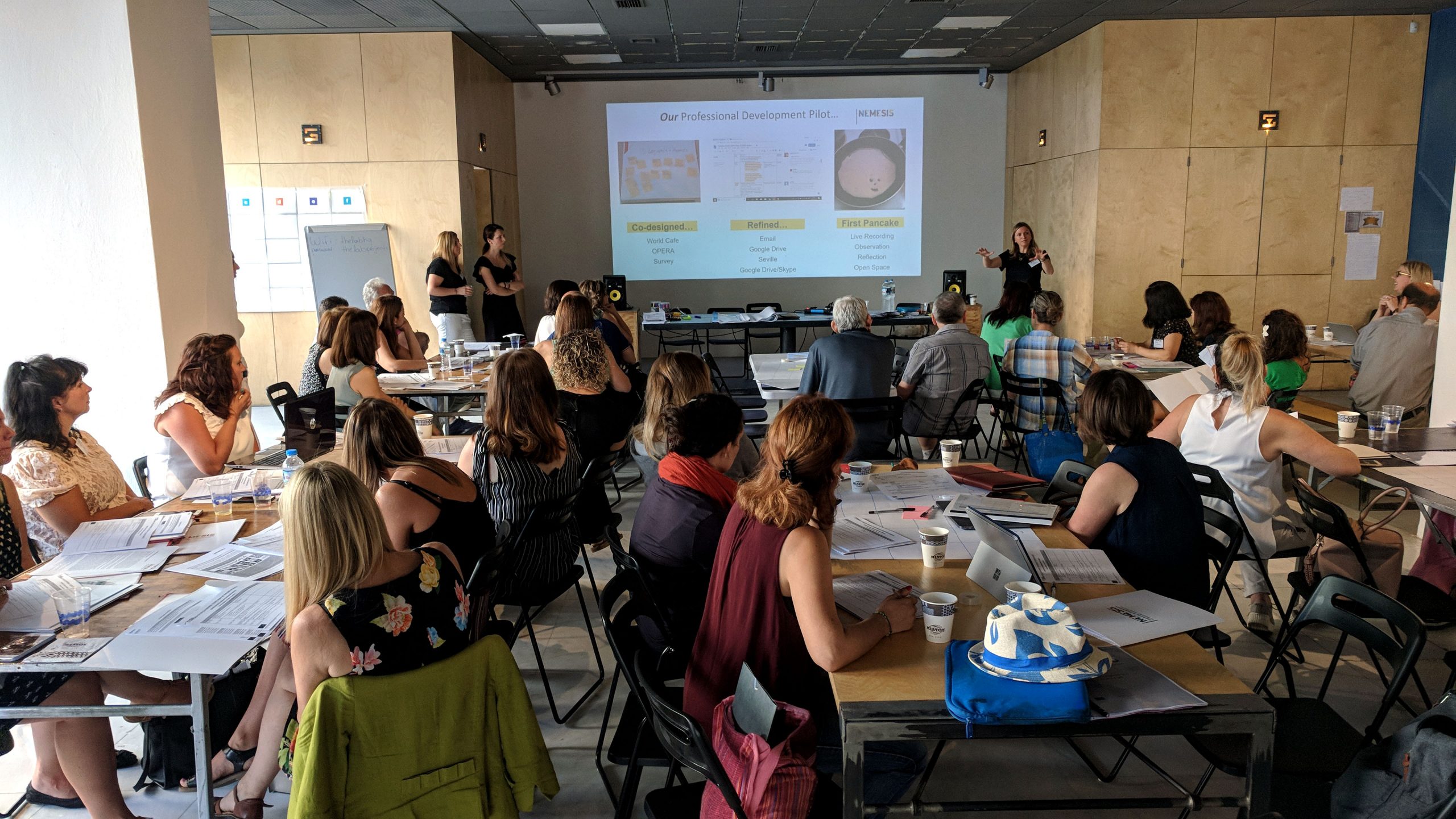

NEMESIS conceived co-creation labs as open learning environments. Here, teachers and students join forces with parents, social innovation practitioners and any other member of the local community to collaborate in the design and development of social innovation projects. You can think of a Co-Lab as the main decision-making structure of the project, bringing together student representatives, teachers and a range of different community actors including families.

Community involvement in NEMESIS

Schools in Pilot 1 have managed to engage a rich mix of community partners. Parental involvement has been a consistent feature in all Co-Labs, particularly in Primary Schools. As observed in the figure below the number of parents (Family) attending Co-Lab meetings is only second to teaching staff. Non-Profit organisations (including SIPs) and Local Authorities do also feature prominently in the Co-Lab Member Lists provided by the schools.

Profile of Co-Lab members

Stakeholders from non-profit sector outnumber the rest

Piloting schools have adopted an expanded approach to stakeholder engagement that goes beyond Co-Lab participation. In total, schools have established fruitful links and worked alongside 92 unique external stakeholders representing a diverse mix of profiles as evidenced in the figure below. Representatives from the non-profit sector (including Social Innovation Practitioners) outnumber the rest of groups. The key input and support provided by local authorities is also worth noting and acknowledging.

Overall Stakeholder Engagement

External stakeholders were mainly sourced by teachers and schools.

“Contacting external stakeholders takes time, effort. It slows things down. Sometimes you need an expert. It would be nice to have a list of contacts.“ – Teacher, Portugal

However, the need to reach local stakeholders is described by one of the teachers:

“It’s not only geographical proximity, but personality, feeling the space is shared, sense of connectedness, belonging to the same community (neighbours)” – Teacher, Spain

New possibilities and practices

Quite interestingly and in spite of the fact that most of them were institutions and individuals from the local area, two out of three external stakeholders had not collaborated with piloting schools before NEMESIS. This indicates access to new cognitive and relational resources opening up new possibilities and practices (Drew, Priestley & Michael, 2016)

Previous collaboration with school

When asked to describe the role played by external stakeholders, schools described it in different terms. In some cases, stakeholders acted as mentors (26) or as collaborators (18) with quite a lot of contact time with the group of students. Some others brought in expert knowledge (14) needed to deal with specific aspects of the project. Inspiration is also fundamental in the initial stages and the SIPs appointed by NEMESIS have excelled at this. Last but not least, local companies have provided goods and services.

Main role of external stakeholders

When asked to rate the level of involvement, schools did not only consider contact time. Some stakeholders were considered as highly involved simply because they provided some relevant input to the project once.

Stakeholders’ level of engagement

Difficulties finding an SIP

The difficulties reported by schools in finding an appropriate SIP was one of the main lessons of this first pilot. There are three key reasons or explanatory factors.

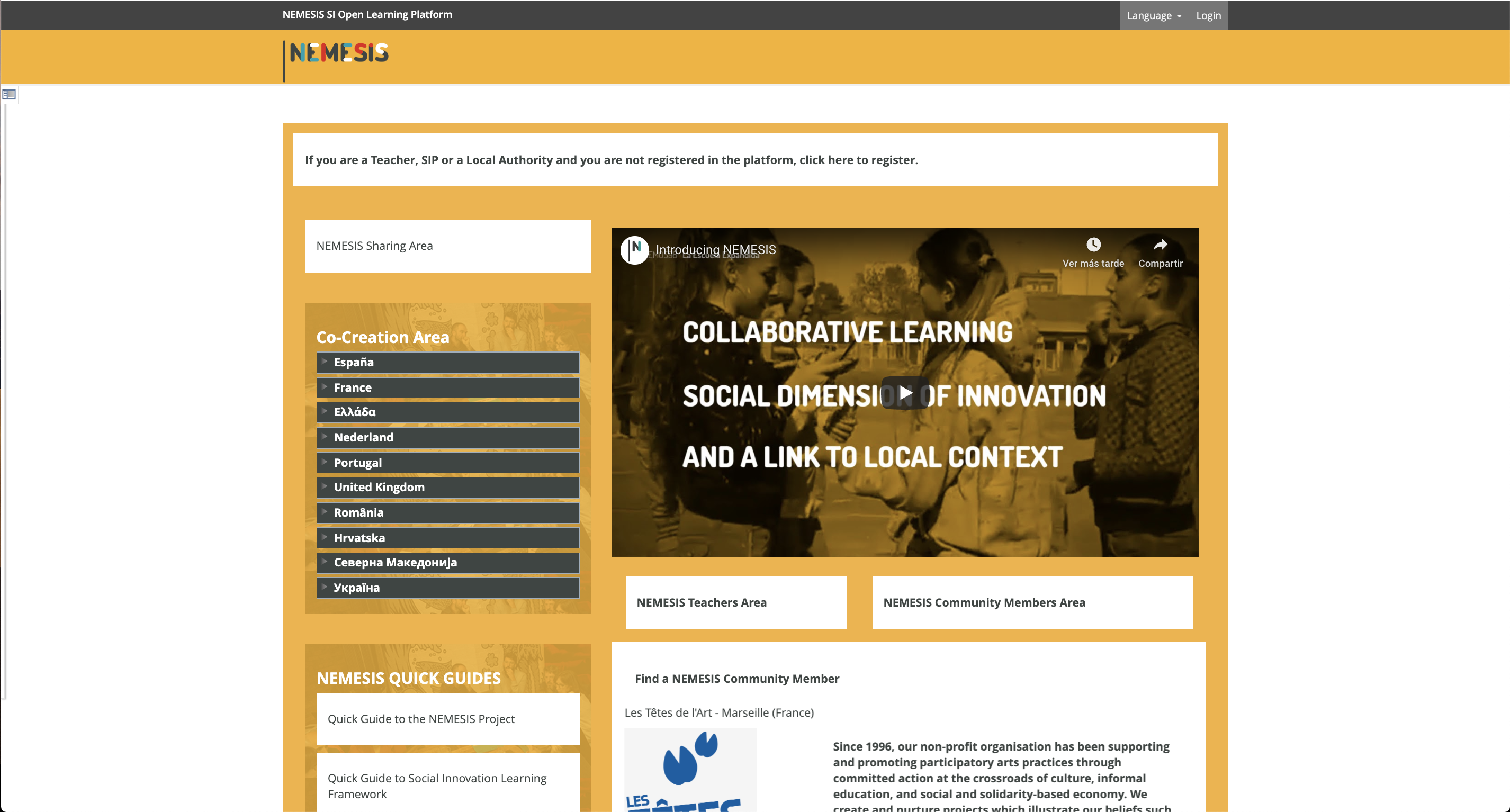

First and foremost, the SIP category is problematic in itself. It is hard to find people who define themselves as Social Innovation Practitioners. In order to overcome this constraint, schools have embraced a more inclusive definition that has informed our decision to rename SIP community as NEMESIS community and include all stakeholders that have community and social focus.

The second aspect has to do with relevance. Schools are expecting to find a good match that is in a position to provide expert advice on the topic they have chosen. Obviously this was (and it’s going to be) hard to anticipate in advance. So while the efforts at creating a SIP community are laudable, they will never meet the unpredictable range of demands arising from school projects.

The local factor has made the difference, evidenced by the strategies devised in schools. So while local community stakeholders are easier to reach, they are also more likely to be concerned and willing to act on issues affecting their communities. Tapping into local community actors does also help to prevent some issues regarding the cost and time of attending Co-Lab meetings or undertaking actions with schools.

NEMESIS enables new, stronger connections with local community

Co-Labs, a central element in NEMESIS pedagogical model, have enabled collaboration between young people and adults to address problems in the school and their local communities and allowed students to have a say in issues of their interest and assume leadership roles in change efforts.

As we have discussed in this article, NEMESIS has enabled new and stronger connections with the local community. A broad range of local stakeholders, mainly sourced by schools, have been engaged in the project. Factors like proximity, relevance and disposition to collaborate on a voluntary basis are key to build a strong NEMESIS community.

Are you a school willing to learn more about NEMESIS or thinking about joining the project? Feel free to surf the web and drop us a line (hello@nemesis-edu.eu) or fill our contact form.

Are you a social innovator who would like to collaborate with the schools in your area? Click here for more info on how to become a mentor.

As such, the competences and values we envision in NEMESIS include self-efficacy and social communication skills but also temper them with empathy and the embracing of diversity and democratic decision-making. Our model promotes problem-solving skills and resource mobilization abilities, but also pairs them with reflective learning and social resilience. In its ethical core, NEMESIS aims to encourage the development of collective capacities for taking innovative actions inspired by key values, such as equality, respect, generosity, trust and altruism. When such results become evident through our collective efforts in the NEMESIS project, we will know that our tree is blooming and is about to bear fruits. Youth activism goes beyond charitable and voluntary work for the community, it aims at influencing policy and institutional practices for the promotion of social justice.

As such, the competences and values we envision in NEMESIS include self-efficacy and social communication skills but also temper them with empathy and the embracing of diversity and democratic decision-making. Our model promotes problem-solving skills and resource mobilization abilities, but also pairs them with reflective learning and social resilience. In its ethical core, NEMESIS aims to encourage the development of collective capacities for taking innovative actions inspired by key values, such as equality, respect, generosity, trust and altruism. When such results become evident through our collective efforts in the NEMESIS project, we will know that our tree is blooming and is about to bear fruits. Youth activism goes beyond charitable and voluntary work for the community, it aims at influencing policy and institutional practices for the promotion of social justice.